Caleb K. Harada

Exomoons Orbiting Temperate Giant Planets

Exomoons are the hypothesized natural satellites of exoplanets, which may hold clues about planet formation, migration, and habitability. Exomoons orbiting temperate giant planets (i.e., planets that are orbiting near the "habitable zone" of their host stars, but are too gas- or volatile-rich to have a habitable surface) are particularly interesting because they are predicted to be stable over long periods of time and could, in principle, support life. Temperate exomoons could dramatically expand the range of "habitable" environments beyond the Solar System, especially considering the tantalizing prospect of icy moons in the outer Solar System being ammenable to life. To date, no exomoon detections have been comfirmed due to both the low expected signal-to-noise and astrophysical systematic uncertainties like stellar variability. Nonetheless, theoretical studies of exomoon stability can place important limits on what we may expect to observe in temperate Jovian systems in the future with more precise technology, as well as informing uncertainties in ultra-precise measurements of exoplanet systems.

Exomoons in the HIP 41378 system

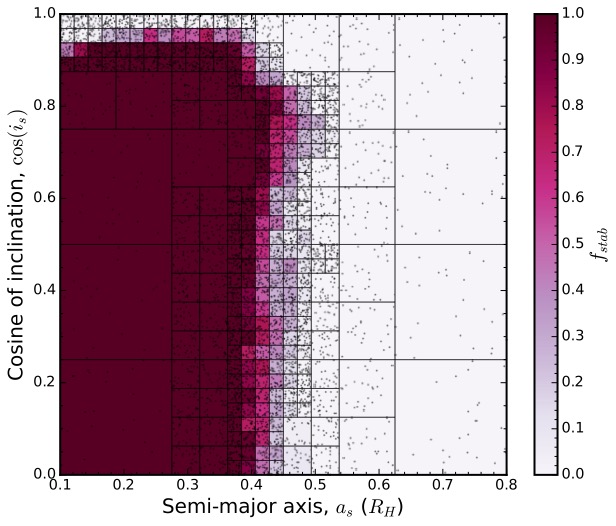

Figure 1. Fractional

stability of the hypothetical exomoon system, shown in the semi-major axis-orbital inclination plane

(Harada et al. 2023).

In Harada et al. (2023), we investigated

the plausibility of exomoons orbiting the temperate giant planet HIP 41378 f,

which has been shown to have a low apparent bulk density and a flat near-infrared transmission spectrum,

hinting that it may possess circumplanetary rings. Given this planet's long orbital period (1.5 yr), it has

been suggested that it may also host a large exomoon. Here, we analyzed the orbital stability of a

hypothetical exomoon with a satellite-to-planet mass ratio of 0.0123 orbiting HIP 41378 f. Combining a

new software package, astroQTpy,

with REBOUND and EqTide, we conducted a series of N-body and tidal migration simulations, demonstrating

that satellites up to this size are largely stable against dynamical

escape and collisions. For example, Figure 1 shows the fraction of simulated N-body systems that were stable

against Hill sphere escape and collisions as a function of the semi-major axis of the moon

and its orbital inclination (relative to planet f).

Figure 1. Fractional

stability of the hypothetical exomoon system, shown in the semi-major axis-orbital inclination plane

(Harada et al. 2023).

In Harada et al. (2023), we investigated

the plausibility of exomoons orbiting the temperate giant planet HIP 41378 f,

which has been shown to have a low apparent bulk density and a flat near-infrared transmission spectrum,

hinting that it may possess circumplanetary rings. Given this planet's long orbital period (1.5 yr), it has

been suggested that it may also host a large exomoon. Here, we analyzed the orbital stability of a

hypothetical exomoon with a satellite-to-planet mass ratio of 0.0123 orbiting HIP 41378 f. Combining a

new software package, astroQTpy,

with REBOUND and EqTide, we conducted a series of N-body and tidal migration simulations, demonstrating

that satellites up to this size are largely stable against dynamical

escape and collisions. For example, Figure 1 shows the fraction of simulated N-body systems that were stable

against Hill sphere escape and collisions as a function of the semi-major axis of the moon

and its orbital inclination (relative to planet f).

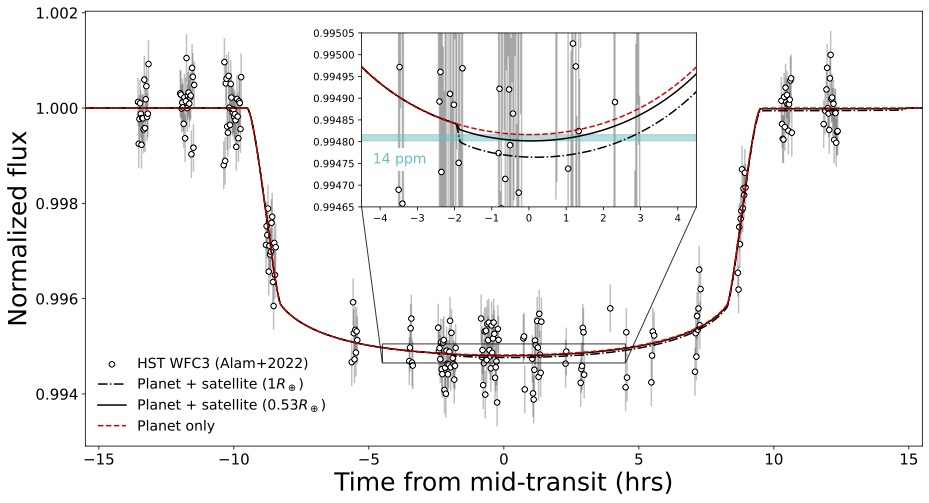

Figure 2. Simulated

exomoon transits compared to the observed white light curve from HST WFC3 (HST GO program 16267). Figure originally published in

Harada et al. (2023).

We also simulated the expected transit signal from this hypothetical exomoon and showed that

current transit observations likely cannot constrain the presence of exomoons orbiting HIP 41378 f, though

future observations may be capable of detecting exomoons in other systems (for example, see Figure 2). Lastly, we modeled the combined

transmission spectrum of HIP 41378 f and a hypothetical moon with a low-metallicity atmosphere, and showed

that the total effective spectrum would be contaminated at the 10 ppm level. This work not only demonstrates the feasibility of exomoons orbiting HIP 41378 f, but also shows that large

exomoons may be a source of uncertainty in future high-precision measurements of exoplanet systems.

Figure 2. Simulated

exomoon transits compared to the observed white light curve from HST WFC3 (HST GO program 16267). Figure originally published in

Harada et al. (2023).

We also simulated the expected transit signal from this hypothetical exomoon and showed that

current transit observations likely cannot constrain the presence of exomoons orbiting HIP 41378 f, though

future observations may be capable of detecting exomoons in other systems (for example, see Figure 2). Lastly, we modeled the combined

transmission spectrum of HIP 41378 f and a hypothetical moon with a low-metallicity atmosphere, and showed

that the total effective spectrum would be contaminated at the 10 ppm level. This work not only demonstrates the feasibility of exomoons orbiting HIP 41378 f, but also shows that large

exomoons may be a source of uncertainty in future high-precision measurements of exoplanet systems.